Chapter 1

1

What is a printed book?

1.1 BRIEF HISTORY OF THE PRINTED BOOK

The history of the book is related to the origin of writing and the inventions of clay tablets, papyrus, rolls, codices, the vellum, paper and the mechanical printing process. The following sections will go briefly on how the book evolved from ancient times (~ 5000 BC) up to today.

1.1.1 Books in Ancient Times (1800 BC – 500 CE)

Clay Tablets

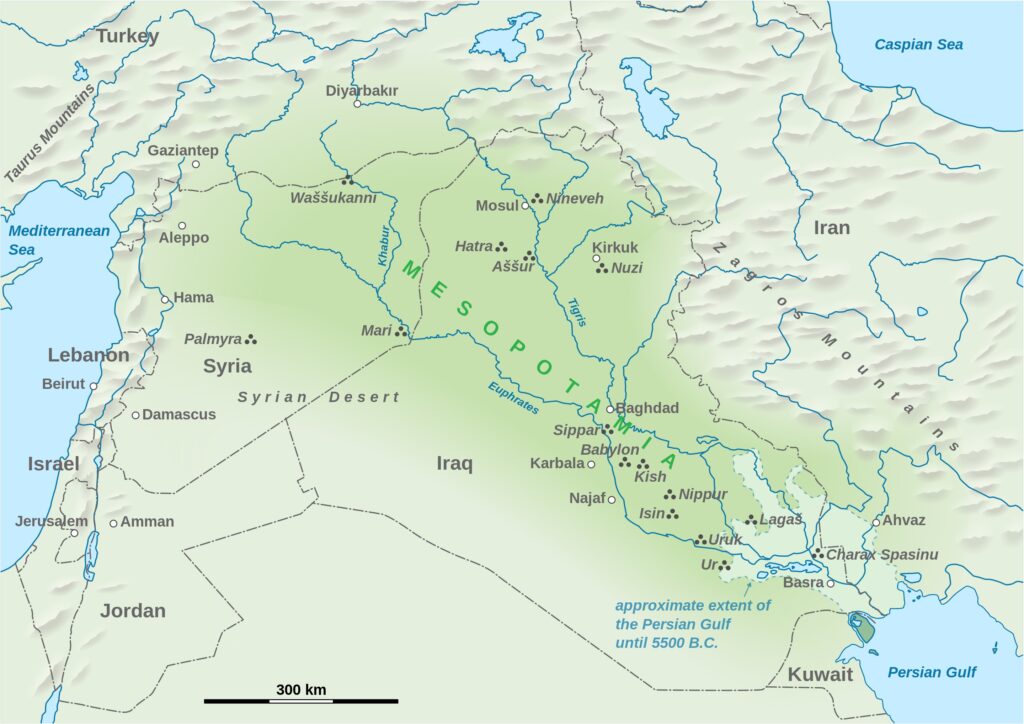

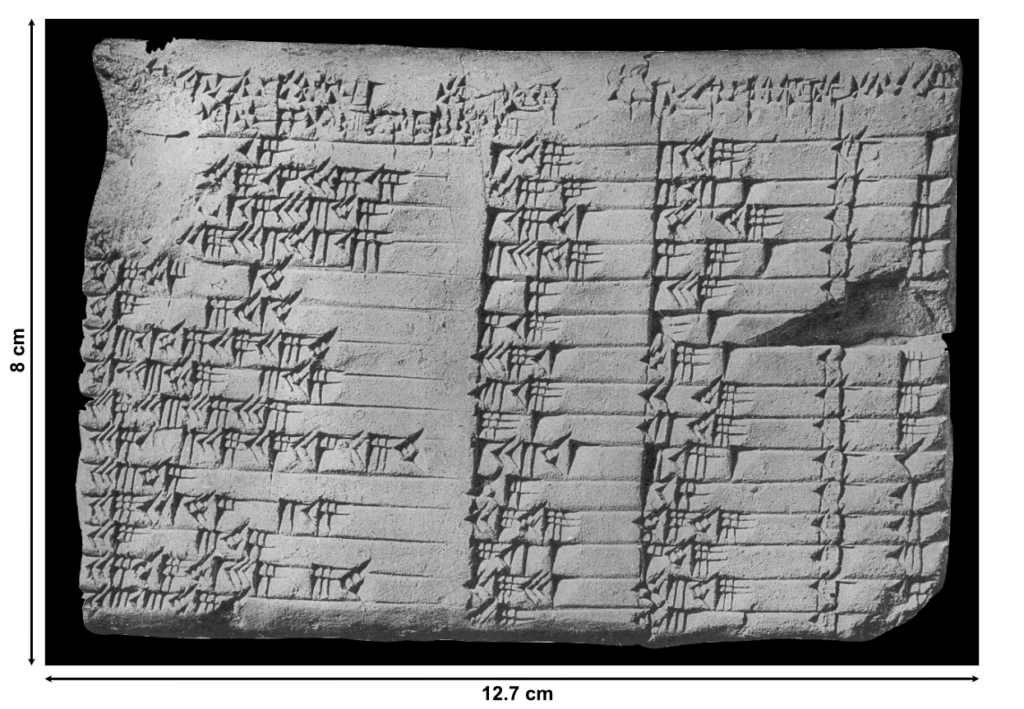

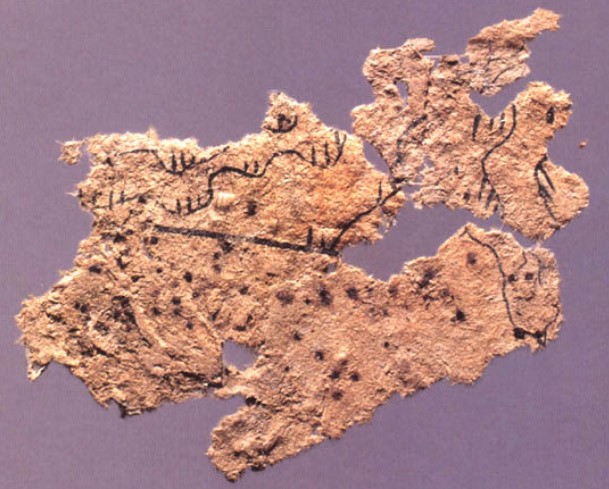

Writing aroused in the setting of temple administration in south cities of Mesopotamia, Sumer (today Iraq), see figure 1.1.1, in late 4th millennium BC. Accountants wrote their records in 1 cm thick 12×8 cm clay tablets. The writing signs were created using a pointed stylus, pressed on a soft mass of clay to form linear strokes or wedges (in latin cunneus), and from this the name of the cuneiform written language. The clay was then baked to make it easier to manupulate. Figure 1.1.2 shows a tablet, named The Babylonian Plimpton 322 tablet, which contains numbers in cuneiform script, believed to have been written in Senkereh (Basra) around 1800 BC.

Papyrus

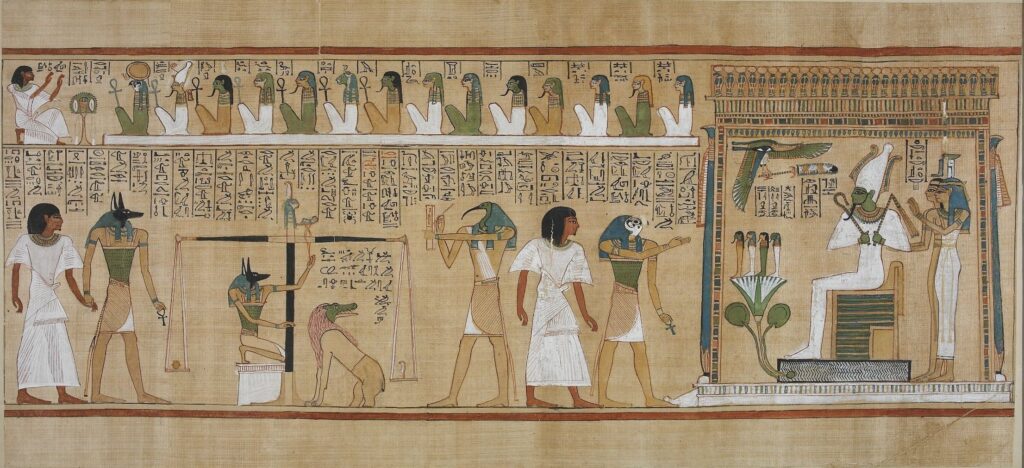

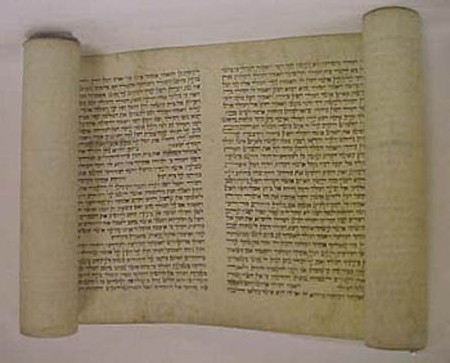

Papyrus was made from the marrow of the papyrus cyperus L plant, which grew around the swamp of the Nile Delta. The stalks of the plant was cut into pieces ~ 30 cm. The pitch was the sliced into strips, and laid side by side, a second layer was then laid at an angle of 90 degrees. The two layers were pressed to get them glued. Figure 1.1.3 show Ancient Egypt were papyrus was created in the 4th century BC. Figure 1.1.4 shows part of Egyptian The Book of Dead, 1275 BC, on papyrus. Figure 1.1.5 shows a roll (volumen in latin) of papyrus containing the Book of Esther, from Seville, Spain. Papyrus scrolls are rolls of papyrus, normally with writing only in the inner side, where the fibers run horizontally, the so called recto side. The scroll is rolled around two vertical wooden axes. The information in the roll has to be read in a sequential manner.

Parchment (sheep or goatskin) / Vellum (calfskin)

Some inhabitants of Mesopotamia in the 8th century BC preferred animal skin (parchment) to clay tablets as a writing surface. Near the first century BC parchment increased in popularity due to the ban of papyrus export dictated by Ptolemy. The process of parchment was refined in the city of Pergamum in the second century BC, giving as a result a much better quality surface to write.

Paper

Cai Lun, an official of the Chinese Han Dynasty court, is considered the inventor of paper and its manufacturing process in the first century CE. Cai came up with the concept of creating paper sheets from of fishnets, old rags, hemp waste, and macerated tree bark. As writing medium paper use was widespread in the 3rd century CE. Paper replaced the use of papyrus by the end of the 10th century AC.

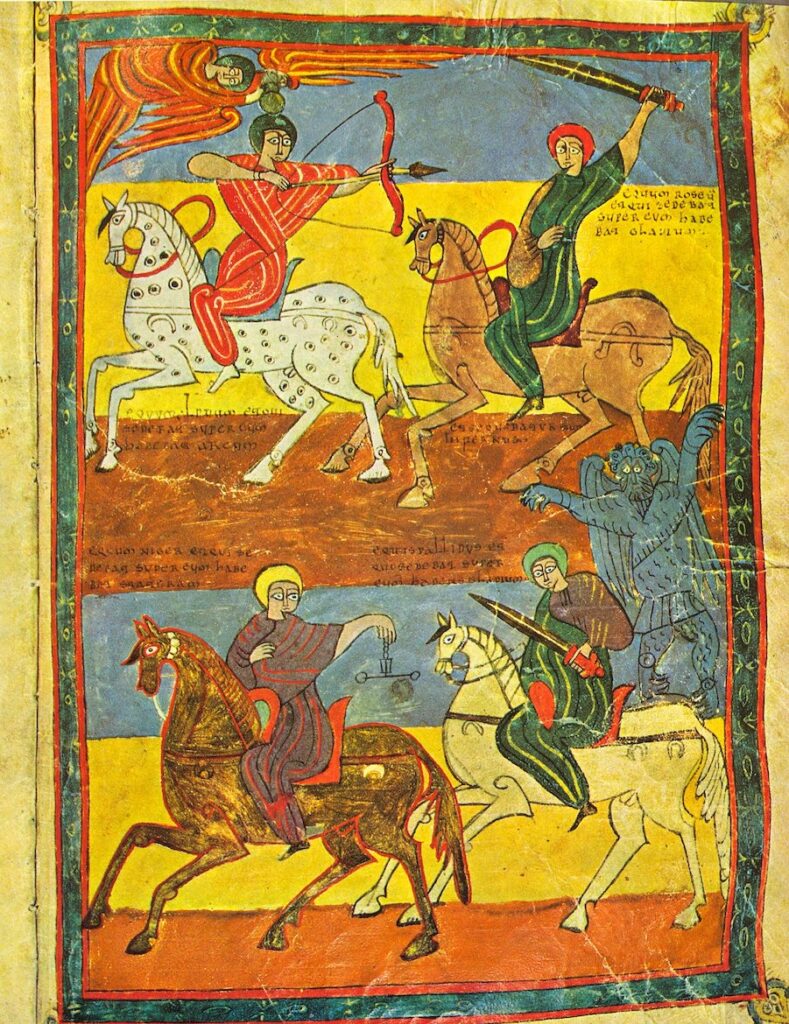

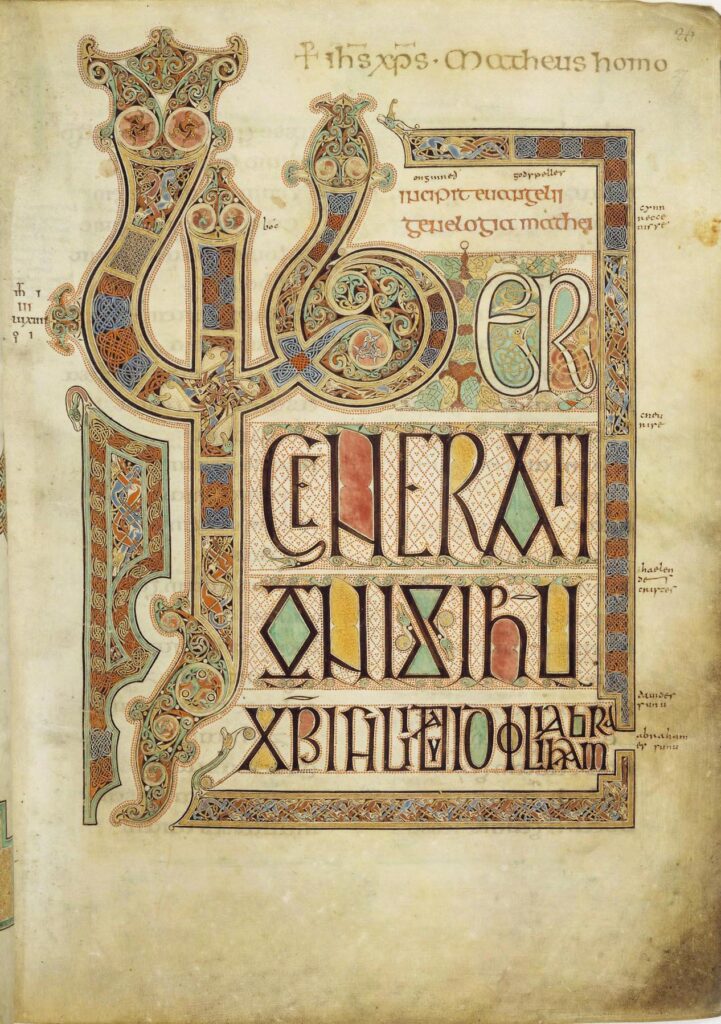

1.1.2 Books in the Middle Ages (500 – 1500 CE)

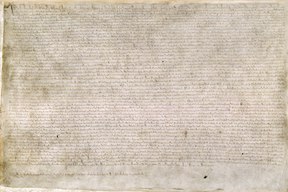

Codex

Between the 2d and 4th centuries, the continuous roll was replaced by the codex, a collection of sheets of parchment (vellum) attached to the back (binding) using different methods. Codex allowed readers to access information on a random manner. Tables of contents, page numbering, and indices allowed for easy access to information.

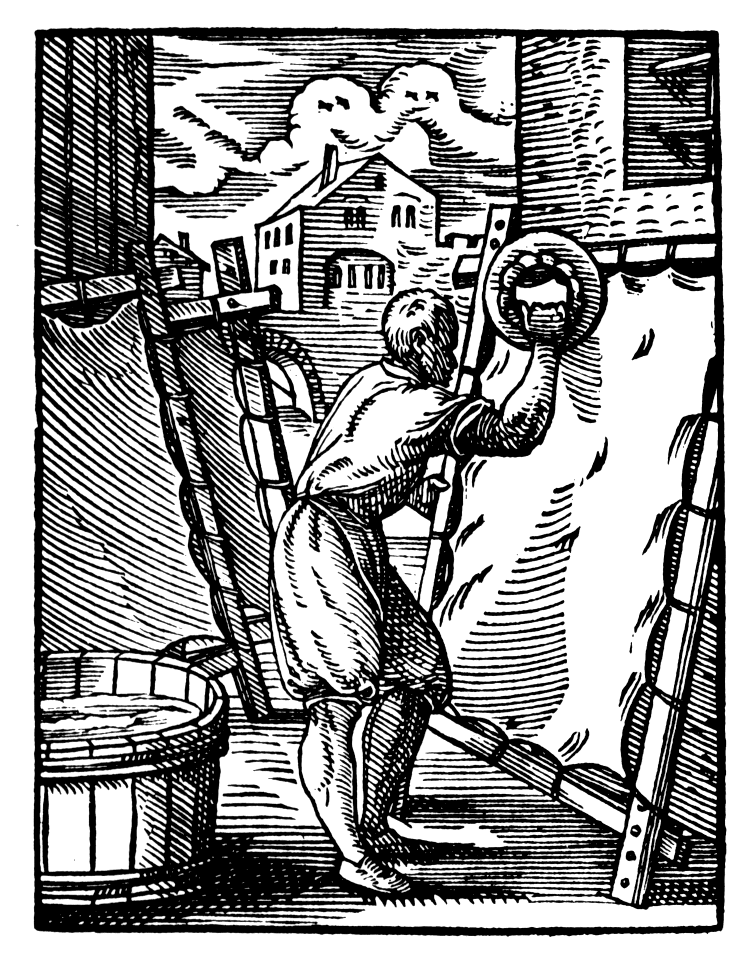

The production process of paper was spread up when water paper mills were developed in Europe in the 11th century AC. This advancement made mass manufacture possible, which brought down the cost of paper, and made books more popular.

In Ancient times books were handwriten. Monks copied, conserved and created in monasteries workrooms, called scriptoriums. In this period the first libraries were created. For example, Vivarum in Calabria, Italy around 500 AC, and Constantine I in Constantinople.

The monastic period of the book came to an end in the 12th century, after the revival of cities in Europe. New structures of book production developed around universities, where reference manuscripts were used by teachers and students.

The first royal libraries appeared, such as Saint Louis and Charles V libraries.

In the Middle Ages, creating a book involved the following steps:

1.1.3 Books in the Renaissance (1500 – 1800 CE)

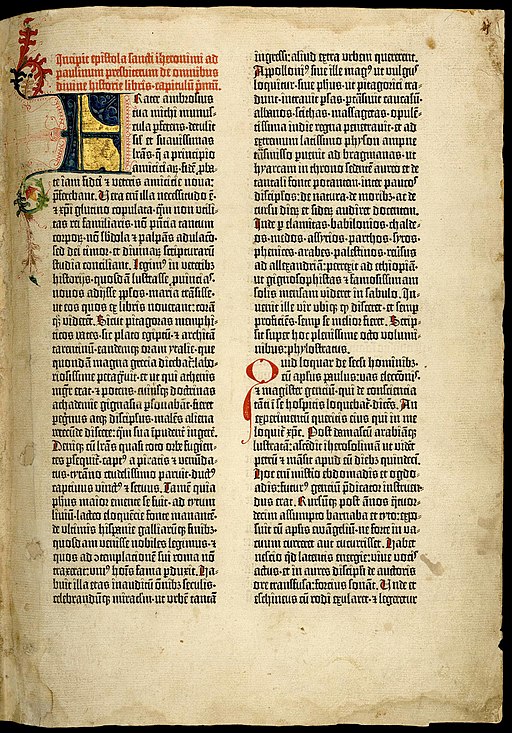

The invention of the mechanical movable type printing press by Johannes Gutenberg around 1440 accelerated the production of printed pages. This invention merged existing technologies—such as the screw press, which was previously used for papermaking—with his original innovation—individual metal letters and punctuation marks that could be individually rearranged—to revolutionize book production. In 1455, he printed 180 copies of the Bible, earning him notable recognition.

With the invention of cast type, lead-tin-antimony type metal, oil-based inks, wooden presses, and paper vehicles, Gutemberg brought effiiency to the book production industry that has lasted for more than five hundred years.

After Gutenberg, books were standardized, plentiful, and relatively cheap to make and disseminate. The increasing middle class’s hunger for knowledge, along with the new availability of classical writings from ancient Greece and Rome, fueled the Renaissance, a period of individual celebration and a shift toward humanism. During this period books started to have titles, similar to what we have today – 2025, pagination and illustrations – images.

After Gutenbergs’ invention, the major innovations the Renaissance saw, were:

- The creation of autonomous type foundries in the sixteenth century.

- The introduction of new typefaces was the most notable innovation.

- The ink production sector had numerous significant breakthroughs throughout the 18th century.

- Alois Senefelder introduced the lithographic process to Germany in 1796. The switch from cast metal types to etched typefaces on films was a significant one.

1.1.4 Modern Era (1800 – Today CE)

Several events occurred at the end of the eighteenth and first half of nineteenth century. The Industrial Revolution (1760 – 1840), the Envangelicalism (1790-1840), and the Napoleonic Wars (1803-1815), triggered the need for innovations in the printing technology. The major innovations were:

Iron Hand Presses: By the end of 1803, Charles, Third Earl Stanhope, planned and oversaw the construction of the first iron printing press.

Steam Powered Presses: The first successful large steam-driven newspaper press was constructed by German bookseller and printer Friedrich Koenig. He collaborated with engineer Andreas Bauer to build two double-cylinder presses for the Times, each with a two-horsepower steam engine.

Mechanized Typecasting: All typecasting was done by hand after Gutenberg’s creation until A. F. Berte created a mechanism in 1807 that pressed the molten metal into the mold using a pump.

Lithographic and Photomechanical Processes: In 1798, a Bavarian named Alois Senefelder created lithography. This innovation, which makes printing from a flat surface possible, is arguably one of the most significant advancements in printing technology.

Paper Rolls Production: The first significant innovation from manual paper making occurred in 1798 when Nicholas-Louis Robert, who was connected to a French paper mill, created a hand-cranked device that generated a continuous roll of paper rather than the usual sheets.

Typewriters: In 1867, Christopher L. Sholes patented the first commercially succesful typewriter. The Remington Company put this typewriter on the market in 1873. The first electric typewriter appeared in 1920. With typewriters people could put together their documents.

Computers: Typewriters were common devices in many offices and homes until 1980 when it was supplanted by personal computers and word processing software. Personal computers and printers, with their associated word processing software allowed people to write their own documents and print them.

The emergence of digital multimedia, which encodes texts, images, videos, animations, and sounds in a distinctive and straightforward form gave birth to the electronic book or ebook. This emergence was one of the major changes that took place in the book publishing industry throughout the 1990s. Information access was further enhanced by hypertext. Lastly, production and distribution expenses were reduced via the internet.

Bibliography

Eliot, S. and Rose, J. (eds.). A Companion to the History of the Book, 2nd edition. Wiley. Hoboken, NJ, 2007.

Kilgour, Frederick. The Evolution of the Book. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998.