Section 2

2

Matter Structure

Matter Structure

At the end of this lesson you should be able to:

- Describe the development of the atomic theory.

- Explain what is an atom and give examples.

- Explain why protons and neutrons are no elementary particles.

- Name the fundamentals forces of nature. Give examples.

- Explain what a molecule is and give examples.

- Explain what a condensed state is and give examples.

2.1 Matter Structure

Introduction

Democritus in the 430th century BC speculated that there was a lower bound on the divisibility of matter and that the least amount of matter were small indivisible particles which he called atoms (from the Greek ατομ meaning indivisible). According to the theory, there was an infinite number of atoms, with different shapes and sizes. The shape of the atoms defined the properties of the substance, according to Democritus. His contemporary, Aristotle, also speculated that matter was made of four elements: Air, Water, Fire, and Earth. Aristotle’s ideas prevailed over those of Democritus for the next two thousand years. In the 1800’s John Dalton (1766-1844) postulated the atomic theory which began the development of what is now accepted. He claimed that atoms of different elements have their own size and mass.

To understand this atomic nature, suppose we have a 7×7 mm piece of silicon (Si). If we look at this piece we would only see a small gray surface, as in figure 2.1. Even if we look at it with the best optical microscope, which would give us approximately a 2,000x magnification, we would still see the gray surface but with a length of 2000 x 7mm = 14000 mm = 14 m. We can even look at the silicon wafer using an electron microscope that gives us a magnification of 1,000,000x and we would still see a gray surface without details. and of a length 7 mm x 1,000,000 mm = 70,000,000 = 7 km.

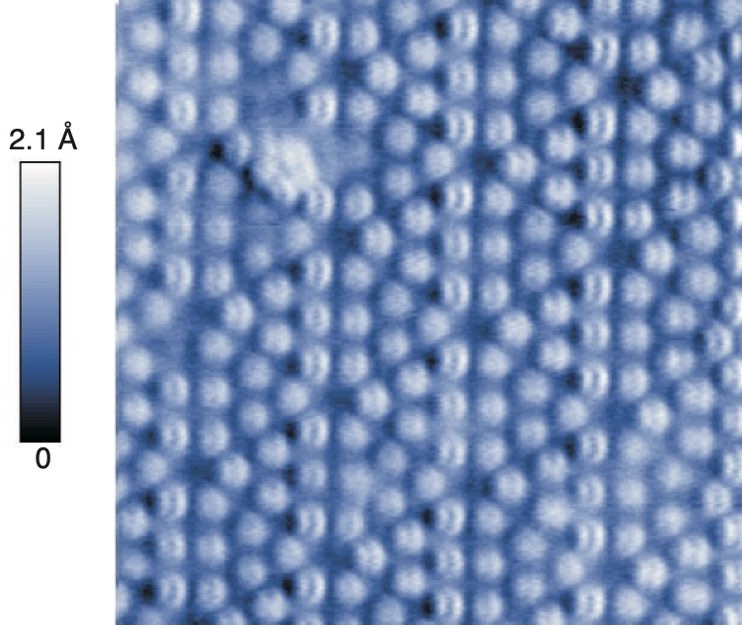

Atomic details can be observed using the AFM (Atomic Force Microscopy) technique. With this technique, individual atoms would look like in Figure 2.2.

Sub-atomic Particles

We currently believe that all matter in the universe is made up of a few elementary particles. All these particles are characterized by having different properties of mass (m), electric charge (q), spin (s), lifetime and other properties that are studied in more advanced courses.

The four most important stable particles up to the beginning of the 19th century were:

The electron (e), discovered in 1897 by J. J. Thompson (1856-1949).

The proton (p), discovered by Ernest Rutherford (1871-1937) in 1917.

The neutron (n), discovered by James Chadwick (1891-1974) in 1932.

The photon (𝛾), whose existence was suggested by A. Einstein in 1905.

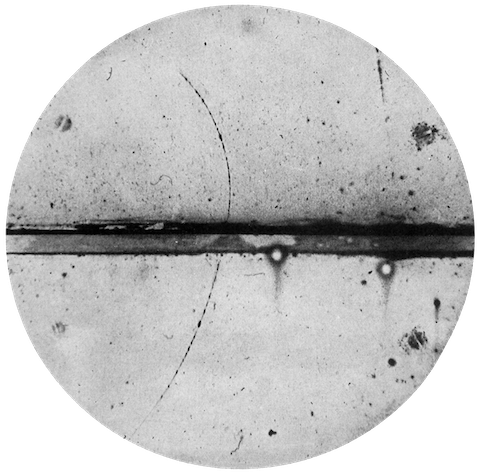

To understand this atomic nature, suppose we have a 7×7 mm piece of Almost all the observed phenomenology in the universe was explained by the interaction between these four particles. However, the formulation of new interaction hypotheses and new experimental techniques in the 20th century, such as particle accelerators (Figures 2.3 and 2.4) and particle detectors (counters) such as cloud chambers (Charles T. Rees Wilson 1911), the bubble chamber (Donald A. Glaser 1960), scintillators, and photomultipliers helped discover new particles that validated the new theories. For example, in 1928 Paul Dirac’s relativistic quantum theory suggested the existence of a particle with the same mass as the electron but with opposite electric charge and spin.

Dirac’s suggested particle was discovered experimentally by Carl Anderson in 1932 and named positron (antiparticle of the electron), Figure 2.5. For this discovery, he was awarded the Noble Prize in Physics in 1936.

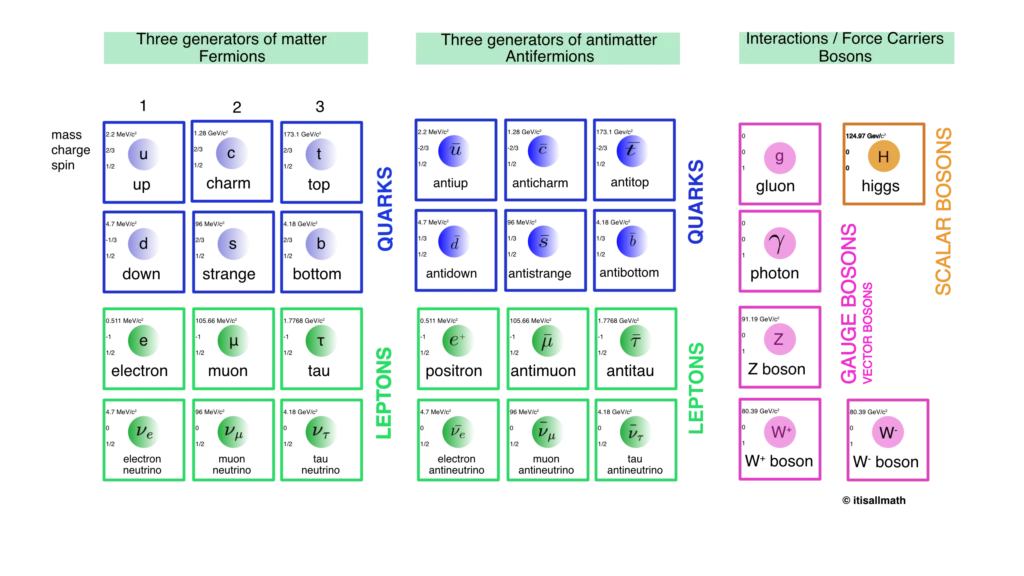

Theory and experiments to date say that protons and neutrons are not elementary but are themselves composed of particles that are currently considered elementary called quarks, of which there are six types with different flavors (u, c, t, d, s, b). Quarks are part of particles called hadrons (from the Greek άδρός meaning strong).

Other type of particles that until today seem to be elementary are leptons (from the Greek λεπτός which means light) and bosons (in honor of Satyendra Nath Bose). To the class of leptons belong the electron (from the Greek ήλεκτρον which means amber), the muon (μ), tau (τ) and its corresponding antiparticles and neutrinos. To the class of bosons belong the photons, the gluon (g, from the English glue, which means glue), and the bosons W+, W–, Z. and H, which are the carriers of the interactions. Figure 2.6 shows the model that classifies all currently known elementary particles.

Fundamental Forces in Nature

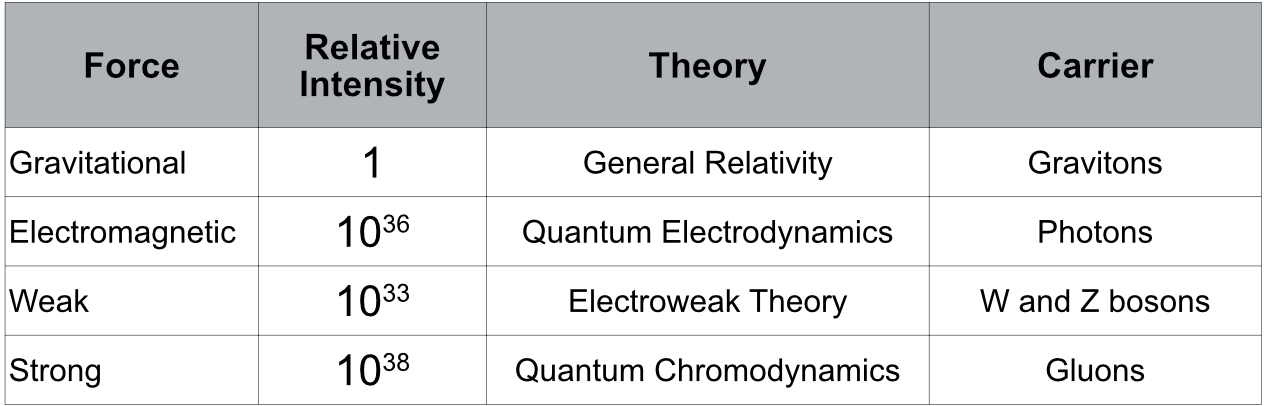

From what we know to date (2023) there are four types of interactions or forces between particles: gravitational, electromagnetic, weak and strong. Table 2.1 shows some characteristics of these forces.

The action of all the fundamental forces is described with the mathematical concept of a field defined at each point in space.

Gravitational interactions are caused by particles with mass or energy. This interaction is far-reaching and explains why celestial bodies move as it has been observed since ancient times. The first formulation of a gravitational theory appeared in Isaac Newton’s Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica (Mathematical Principles of Natural Philosophy) in 1687.

Electromagnetic interactions are in turn caused by particles that have aproperty called electric charge. This interaction is far-reaching. There are two types of charge: positive and negative. Charges of the same type repel and charges of different types attract. The magnitude of the force is inversely proportional to the square of the distance between the charges. That is to say that at small distances the intensity of the force is great and decreases with increasing distance. Electricity was known in ancient times from the friction of some objects with others, such as amber and rabbit fur. However, its causes were not known. It was not until 1600 that the English scientist William Gilbert published De Magnete, a work in which he began to formulate theories about magnetism and electricity. These theories reached great maturity with the publication of A Treatise on Electricity and Magnetism by Jame C. Maxwell in 1873.

The weak nuclear forces are caused by the flavor property of quarks. The interaction is of very short range, 10-17 m, and is responsible for beta decay in which some unstable nuclei emit β particles (electrons or positrons with high energy).

Gravitational interactions are caused by particles with mass or energy. This interaction is far-reaching and explains why celestial bodies move as it has been observed since ancient times. The first formulation of a gravitational theory appeared in Isaac Newton’s Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica (Mathematical Principles of Natural Philosophy) in 1687.

Electromagnetic interactions are in turn caused by particles that have aproperty called electric charge. This interaction is far-reaching. There are two types of charge: positive and negative. Charges of the same type repel and charges of different types attract. The magnitude of the force is inversely proportional to the square of the distance between the charges. That is to say that at small distances the intensity of the force is great and decreases with increasing distance. Electricity was known in ancient times from the friction of some objects with others, such as amber and rabbit fur. However, its causes were not known. It was not until 1600 that the English scientist William Gilbert published De Magnete, a work in which he began to formulate theories about magnetism and electricity. These theories reached great maturity with the publication of A Treatise on Electricity and Magnetism by Jame C. Maxwell in 1873.

The weak nuclear forces are caused by the flavor property of quarks. The interaction is of very short range, 10-17 m, and is responsible for beta decay in which some unstable nuclei emit β particles (electrons or positrons with high energy).

Gravitational interactions are caused by particles with mass or energy. This interaction is far-reaching and explains why celestial bodies move as it has been observed since ancient times. The first formulation of a gravitational theory appeared in Isaac Newton’s Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica (Mathematical Principles of Natural Philosophy) in 1687.

Electromagnetic interactions are in turn caused by particles that have aproperty called electric charge. This interaction is far-reaching. There are two types of charge: positive and negative. Charges of the same type repel and charges of different types attract. The magnitude of the force is inversely proportional to the square of the distance between the charges. That is to say that at small distances the intensity of the force is great and decreases with increasing distance. Electricity was known in ancient times from the friction of some objects with others, such as amber and rabbit fur. However, its causes were not known. It was not until 1600 that the English scientist William Gilbert published De Magnete, a work in which he began to formulate theories about magnetism and electricity. These theories reached great maturity with the publication of A Treatise on Electricity and Magnetism by Jame C. Maxwell in 1873.

The weak nuclear forces are caused by the flavor property of quarks. The interaction is of very short range, 10-17 m, and is responsible for beta decay in which some unstable nuclei emit β particles (electrons or positrons with high energy).

Strong nuclear interactions are caused by the color property of quarks. This force is short-range and is what keeps protons and neutrons in the atomic nucleus, despite the electrical repulsive force between the protons. Even at smaller distances, this force is what keeps quarks inside neutrons and protons.

Atoms

According to today’s (2023) physical theories, every material object in nature is made up of atoms, and these in turn are made up of sub-atomic particles that interact with each other.

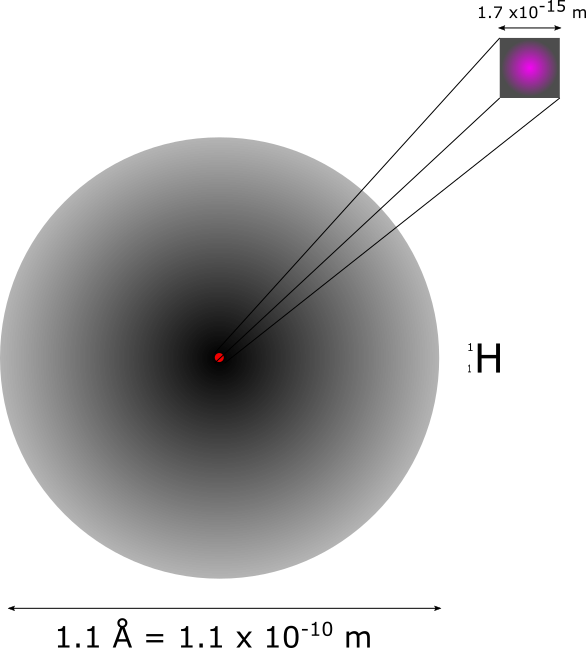

All atoms have a central volume, called the atomic nucleus, of radius about 1 femtometer or 10-15 m, which contains protons and neutrons. Protons and neutrons are confined to the nucleus by the strong nuclear forces. Around the nucleus there are spatial layers, called shells, in which the electrons can be with certain probability. Those electron shells, electron clouds or orbitals have a radius of about 1 picometer or 10-12 m. Electrons are attracted to the nucleus by electromagnetic forces.

Figure 2.7 shows the atomic structure of the hydrogen atom, which has a nucleus with a proton in it, and a spherical shell where the electron is. Atoms in their natural form are electrically neutral, that is, they have the same number of electrons and protons. If an atom has more or fewer electrons than protons, then it is called an ion. Anion if it is positive or cation if it is negative.

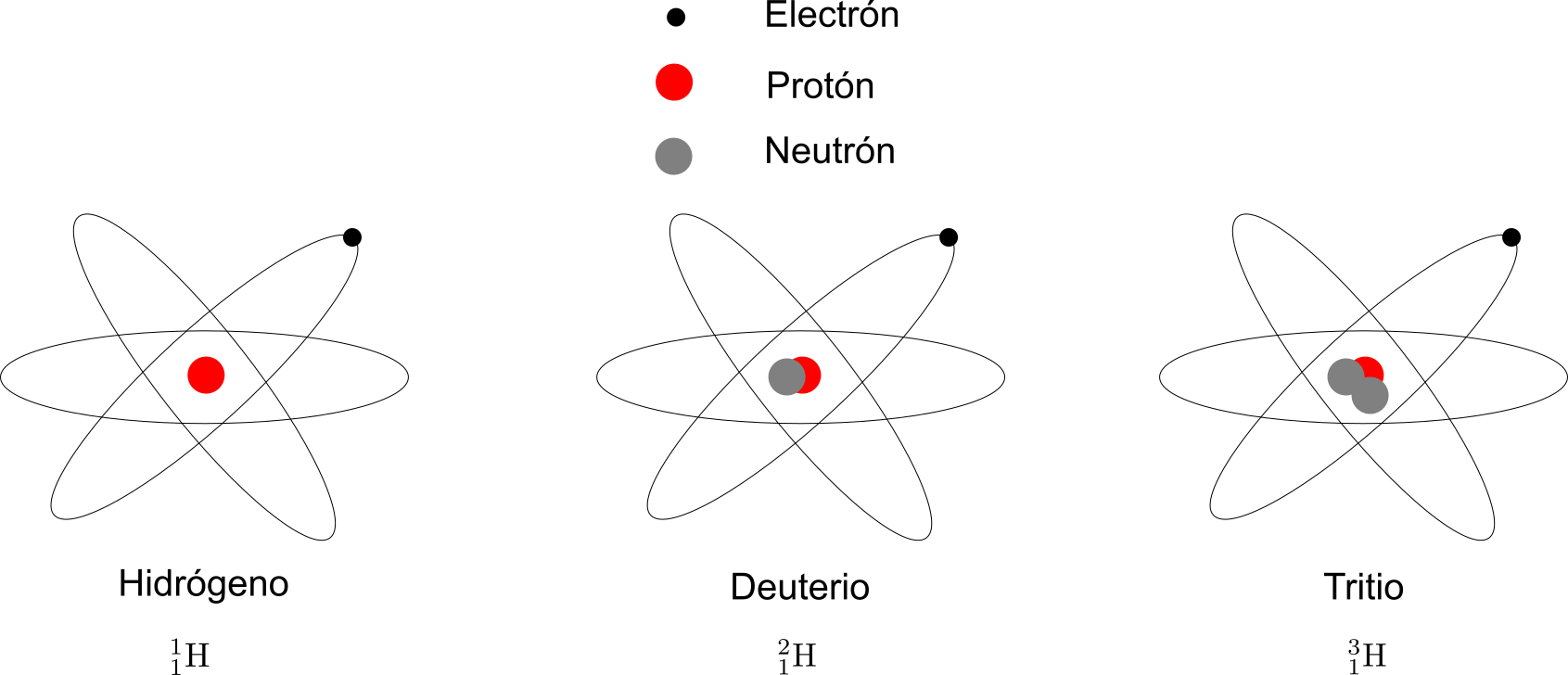

The number of protons in an atom is called the atomic number (Z from the German word zahl meaning number). The number of protons and neutrons in an atom is called the atomic mass and is symbolized by the letter A. Nuclei with different atomic numbers are called elements and are usually represented by the name of the element and the superscript atomic mass and atomic number as a subscript in front of the element name . For example, Uranium is represented by .

There are nuclei with the same number of protons but different numbers of neutrons. For example, there are nuclei of hydrogen with a neutron, called deuterium, and there is also a nucleus of hydrogen with a proton and two neutrons, called tritium. Nuclei with the same atomic number but different atomic masses are called isotopes. Deuterium and Tritium are isotopes of hydrogen, as in Figure 2.8.

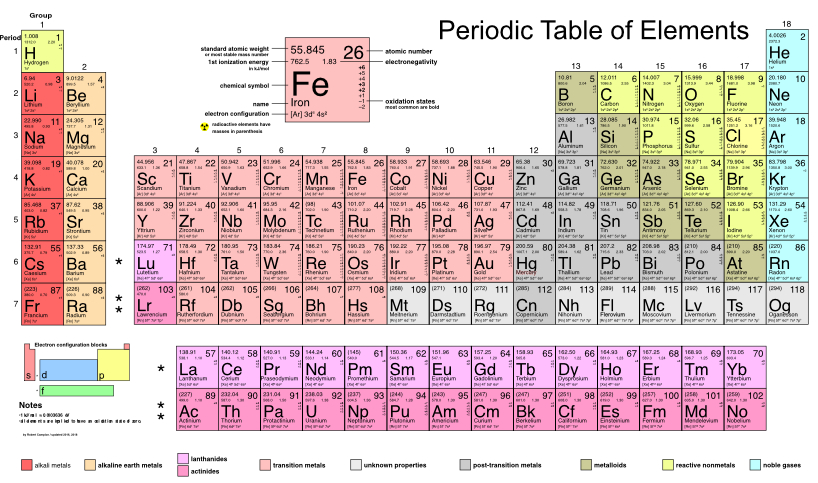

The electromagnetic interaction between the charges of the electron and the proton is what allows the formation of more complex systems of atomic nuclei and electronic clouds. Until 2021, 118 elements were known, some discovered naturally and others artificially synthesized in laboratories. The elements are presented in a rectangular arrangement called the periodic table of the elements. The first 94 elements from Hydrogen, to Plutonium, occur naturally. Elements from Americium, , to Oganeson, , have been synthesized in the laboratory.

The periodic table has 7 rows, called periods, and 18 columns, called groups. The periods contain metals on the left and non-metals on the right. The groups contain elements with similar chemical behavior, due to the way in which the electrons are configured around the nucleus. The elements go in increasing order of atomic number from 1, for Hydrogen, to 118, for Oganeson, as shown in Figure 2.9.

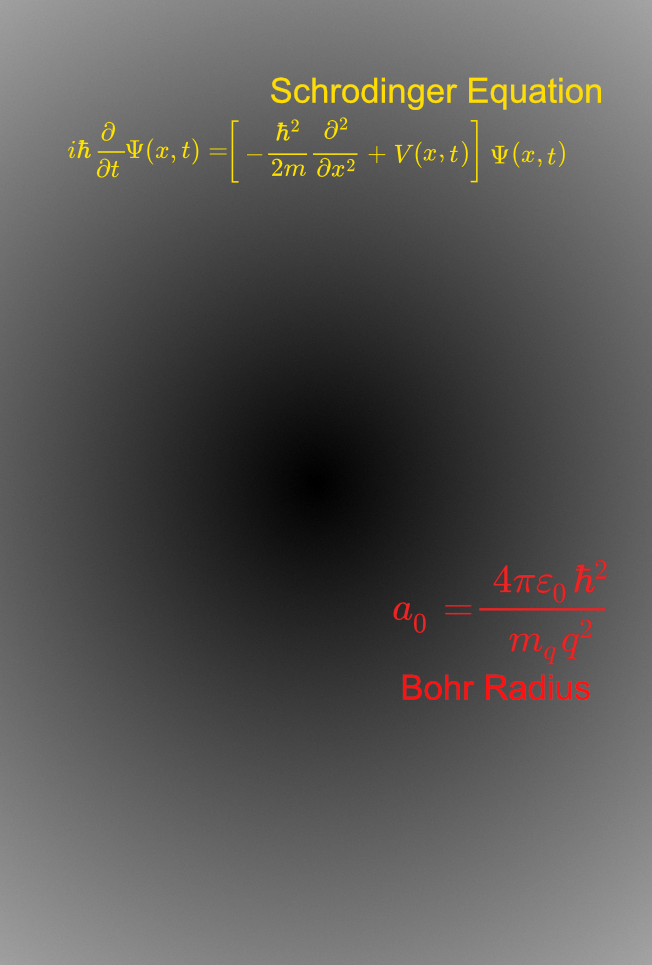

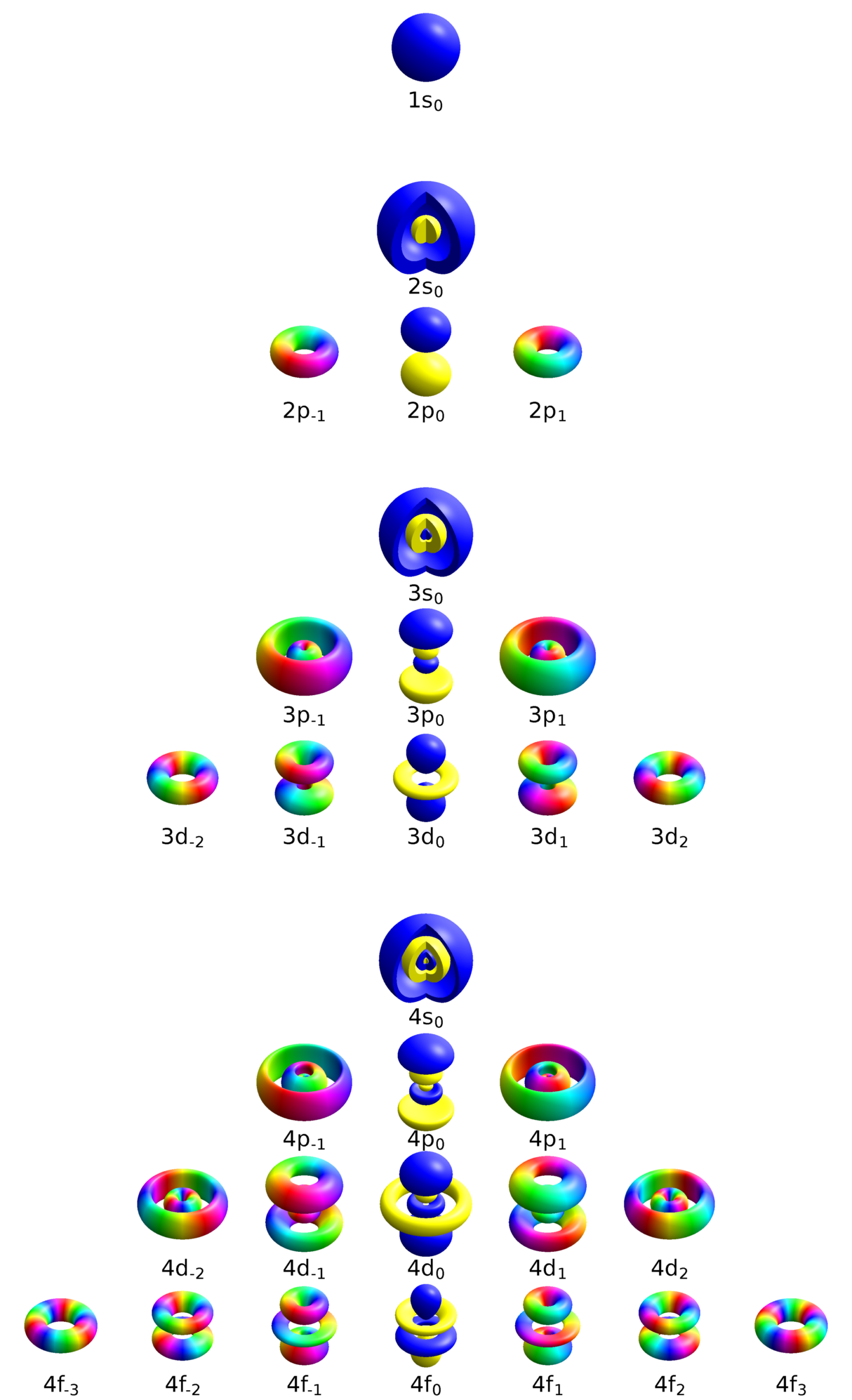

Quantum mechanics dictates the rules on how electrons are distributed around the nucleus. There are regions of space where there is a greater probability that electrons may be. These regions called electron orbitals (s, p, d , f) have different characteristics depending on four quantized values: the distance from the nucleus (quantum number n), the value of the angular momentum (quantum numbers l and ml) and their spin (the quantum number ms). The electrons located in the last orbital of an atom are called valence electrons. These electrons are involved in the formation of bonds in structures of several atoms, called molecules.

Figure 2.10 shows the orbitals of hydrogen-like atoms, that is, atoms that can be modeled as a nucleus surrounded by a single electron, such as He+, and Li2+.

Atomic orbtal n123 eigenstates by Geek

The ionization of atoms is a process by which the atom loses or gains electrons. The process can be initiated by raising the temperature, bombardment with other atoms or light, or by interaction with other elements, such as water. For example, the mixture of salt in water produces Na+ and Cl– ions, with the help of the intervention of water molecules. Positively charged ions like Na+ are called cations. and those with a net negative charge, anions, such as Cl–.

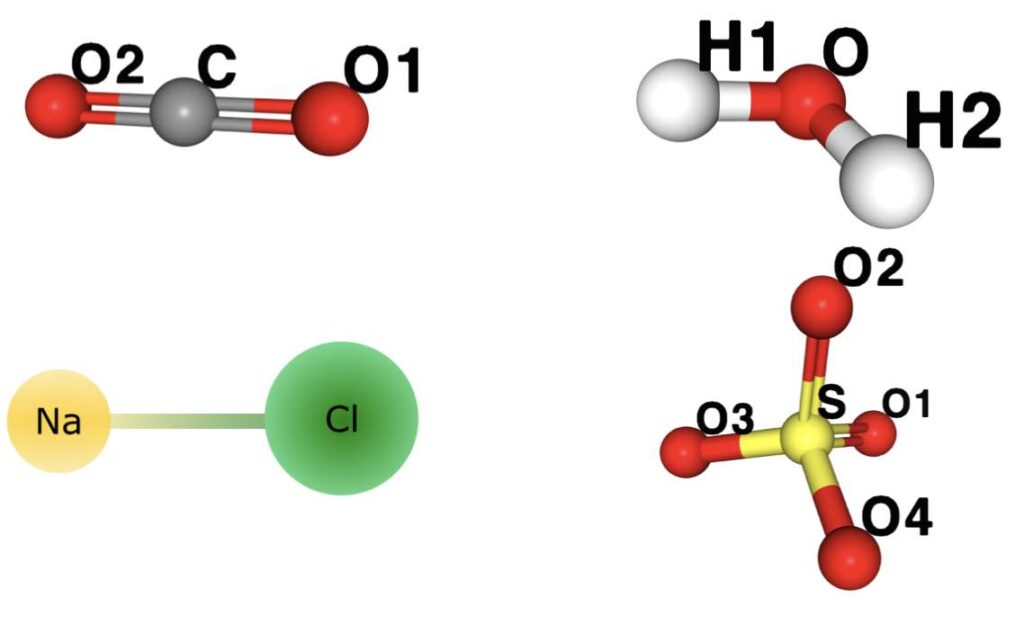

Molecules

Any formation of groups of atoms is called a molecule, such as carbon dioxide, CO2, which is made up of one carbon atom and two oxygen, water, H2O, made up of two hydrogen atoms and one oxygen atom, salt or sodium chloride NaCl composed of one sodium atom and one chlorine atom. Finally the molecule of the sulfate ion (SO4)2- composed of one sulfur atom and four oxygen atoms, two of them with an extra electron, as in the figure 2.11. As you can see, molecules can be electrically neutral or have an electrical charge, in which case they are called ionic molecules.

The union of the atoms that make up a molecule is carried out through chemical bonds, of which there are two of great importance, ionic bonds and covalent bonds.

The ionic bonds are made by the electrical attraction of two ionized atoms, just as occurs in the NaCl salt molecule.

Every atom in the periodic table has two important properties that define how they can be ionized, either by losing electrons, and thus becoming cations, or by acquiring electrons, and thus becoming anions. The properties that make this possible are ionization energy and electronegativity.

Ionization energy is the minimum amount of energy needed to remove the most loosely bound electron from the atom. The larger Z is, the easier it will be to remove the electrons, since the electromagnetic force from the nucleus is shielded by the electronic orbitals of the atom, that is, the valence electrons see a decreased net electrical charge of the nucleus.

The electronegativity of the elements is the tendency that they have to release electrons (or their electronic density) or acquire them. This property depends on its atomic number Z, and the distance from the valence electrons, those found in the orbitals farthest from the nucleus.

In other molecules, the bonds are due to the fact that the atoms that make up the molecule share valence electrons with the help of the coupling interaction of their spins. This type of bond is called a covalent bond, and it occurs in molecules such as methane, CH4.

Condensed Matter

All matter observed in nature is made of the elements of the periodic table, but they usually occur in different forms or phases, depending on the constituent elements, their quantity, density, pressure, and temperature. The number of atoms in an observed piece of material is on the order of 1023 atoms, so they are complicated systems to describe and study due to the large number of elements that interact with each other.

Historically, four states of matter have been described: the solid state (for example, rocks), the liquid state (for example, water), the gaseous state (for example, air) and the plasma (the gas in a neon lamp). The distinction of these states was based on certain distinctive characteristic properties such as their expansion capacity. But there are other states of matter that most have been able to observe in their daily lives. States such as colloids (aerosols), polymers (natural rubber), foams, jellies, granules, liquid crystals, and muscle tissue.

Solids and Liquids

The use and mastery of materials in a condensed state has been of vital importance in the development of civilization. So much so that there have been periods called according to the technology dominated: the stone age, the bronze age, the iron age and recently the plastic age.

Until the end of the 19th century the principles of the macroscopic properties of matter had firm foundations. Thermodynamics, hydrodynamics, and elasticity gave a good description of the static and dynamic properties of gases, liquids, and solids. The new quantum and relativistic theories with the corresponding experimental and probing techniques gave rise to new theories of the solid state being formulated. In this way, the conventional area of solid state physics was formed, which gave many advances in the understanding of electronic band theory, on which the understanding of metals, insulators and semiconductors is based.

The second half of the 20th century brought a number of new models to the physics of cluster states. These new paradigms contributed a framework to describe what we now call condensed-state phases: liquid crystals, superfluids, quasicrystals, one- and two-dimensional systems, as well as the classical phases of liquids and the solid state with their regular shapes.

Condensed matter physics is a field of physics that studies the physical properties of matter whose density is such that intermolecular or atomic forces are strong and determine the properties of the substance.

Condensed matter physics is a field of physics that studies the physical properties of matter whose density is such that intermolecular or atomic forces are strong and determine the properties of the substance.

Soft Matter

This subbranch of condensed matter studies the systems that can be altered by pressure or temperature variations of the order of their thermal fluctuations. Soft matter includes liquids, colloids, polymers, foams, gels, granules, liquid crystals, meat, and other biological materials.

One of the characteristics of the soft states of matter is their ability to self-organize and form states of mesoscopic scales, that is, sizes ranging from nanometers (some atoms as molecules) to micrometric scales. Many of the characteristics of soft matter cannot be predicted from its atomic or molecular components. The characteristics of soft matter are a consequence of mesoscopic states and their interactions.

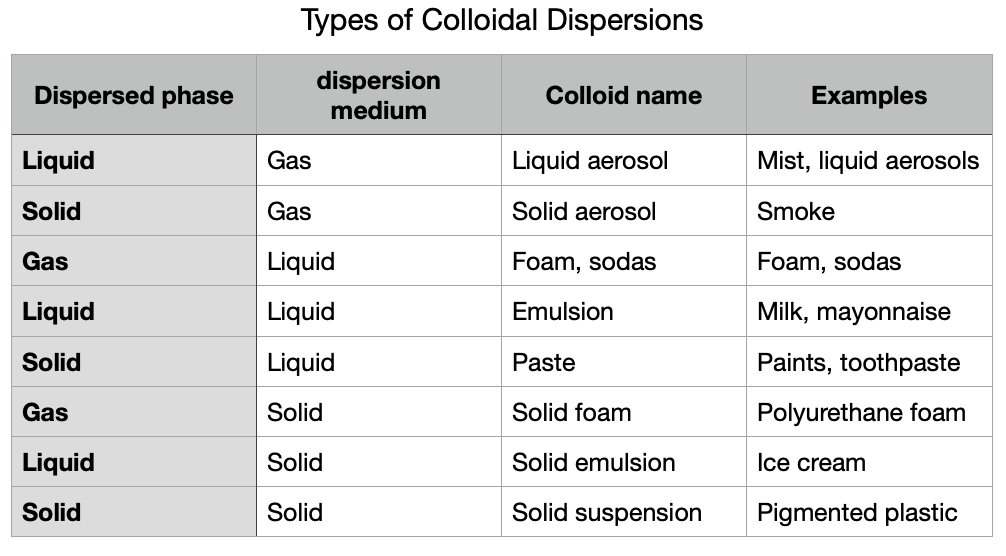

Matter in a liquid state maintains its volume, but adapts to the shape of the container that contains it. Its components, although linked to each other, can move. Perhaps the most essential characteristics of liquids (and gases) is that their density ρ = m / V (the mass per unit volume) is homogeneous and isotopic and that their constituent elements have no order compared to the translational order of the solids. Common examples of soft matter are water, milk, blood, vegetable oil, and gasoline. Table 2.2 shows the types of colloids found in nature.

A colloid is a mixture in which one substance is dispersed evenly throughout another, but the particles of the dispersed substance are larger than those in a solution (like salt in water), yet too small to be seen with the naked eye. Colloids consist of two phases: the dispersed phase (the particles) and the continuous phase (the medium in which the particles are dispersed).

The particles in a colloid typically range in size from about 1 nanometer to 1 micrometer. Because of this size, they do not settle out over time like particles in a suspension (like sand in water), nor do they dissolve like solutes in a solution. Instead, they remain evenly distributed throughout the medium.

Examples of colloids include:

- Foams: such as shaving cream or whipped cream (gas dispersed in a liquid)

- Gels: like jelly (liquid dispersed in a solid)

- Aerosols: such as fog or smoke (liquid or solid dispersed in a gas)

- Emulsions: like mayonnaise (liquid dispersed in another liquid)

In a colloidal mixture, light may scatter off the particles, a phenomenon known as the Tyndall effect, which distinguishes colloids from true solutions.

Solid Matter

Matter in the solid state maintains its constant shape and volume under standard conditions of pressure and temperature, that is, T= 24 ºC and atmospheric pressure P = 1 atm.

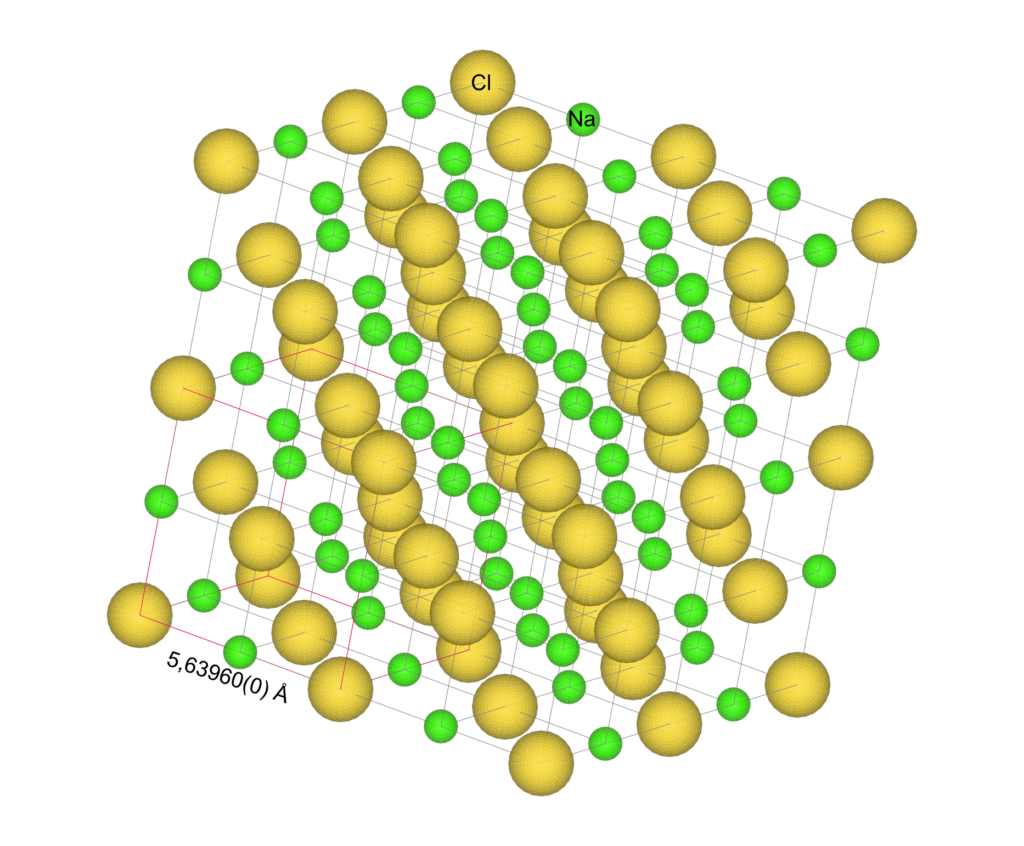

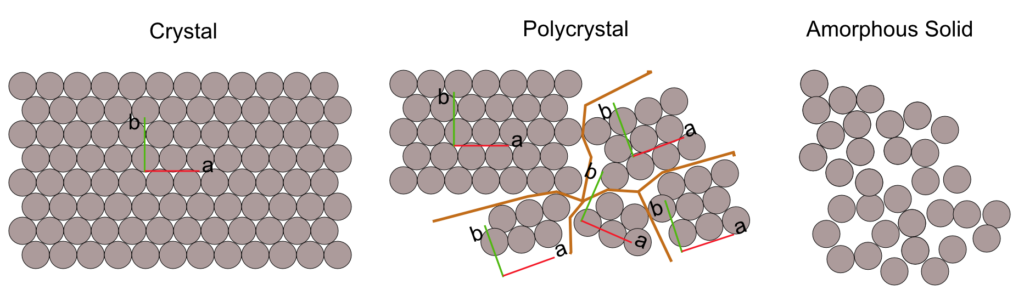

The components of solid matter maintain fixed positions due to their atomic and molecular interactions. It is known that solid materials are organized in such a way that a unit (unit cell) is repeated in space creating what is called the crystal lattice, as shown in figure 2.12.

n this case, the chlorine atoms are represented by reduced yellow spheres at the vertices and faces of an FCC cube (Faced Centered Cubic) with an edge of 5.6369 Å. Likewise, sodium atoms are located at the vertices and faces of a cube with the same edge, but half of the edge translated in the xyz directions. These structures show a definite translational symmetry and thus their order reaches large distance ranges compared to the dimensions of their unit cell.

Solid state physics studies the physical properties (for example, electrical, dielectric, magnetic, elastic, and thermal) of solids in terms of basic physical laws.

In semiconductor technology in 2021, wafers (circular sheets) of crystalline silicon with a diameter of ~ 450 nm are produced. The magnitude of the translation vector of the silicon crystal lattice is 0.543 nm, that is, the length of the wafer diameter is 829 million unit cells.

Many of the solids in nature appear in polycrystalline form, that is, agglomerates of crystalline structures called grains have random directions as shown in Figure 2.13.

Gases

A gas is an agglomerate of molecules, with the particularity that its components, whether they are atoms or molecules, are not linked to each other. That is why gases vary their volume and shape to the container that contains them. For example, in its natural state, hydrogen appears as a molecule of two linked H2 atoms. However, each molecule retains its individuality, they behave as independent particles from the others. Under standard conditions of pressure and temperature, that is, T= 24 ºC and atmospheric pressure P = 1 atm. The distance between the components of the gas is much larger than the size of the components. In the case of monatomic gases (for example Neon Ne). the distance between the atoms is much greater than 10-10 m =1 Å.

Hydrogen is the lightest element on the periodic table and the most abundant in nature. It was discovered by Henry Cavendish (1731-1810) in 1766 as a product of the reaction of metals and acids and he gave it the name flammable air, due to its flammability. In 1783 Antoine Lavoisier gave it the name hydrogen (from the Greek υδρο-water and γενής-genes or water-former). Since gases are not visible to the naked eye, their study began to be done with the help of four macroscopic properties: temperature, pressure, volume, and number of particles. These properties were studied by Robert Boyle (1627-1691), Jacques Charles (1746-1823), John Dalton (1766-1844), Joseph Gay-Lussac (1778-1850) and Amedeo Avogadro (1776-1856).

Video1. Simulation of the diffusion of a gas in a chamber with two compartments.

Plasma

Plasma is perhaps the most abundant state of matter in nature, due to the high pressure and temperature conditions that exist in stellar systems. Matter in the plasma state is a gas with the particularity that there are charged particles that can move in the electric and magnetic fields created by the charged elements of the gas, or in electromagnetic fields created externally. The first plasma studies were carried out by Irving Langmuir around 1920. The studies were carried out in gas discharges in evacuated tubes, filled with gas and subjected to electric fields between electrodes, as shown in figure 2.14.

Neon discharge lamp. Original Centurion work.

The effects of electromagnetic fields on plasma are used in plasma televisions and in systems for the selective decomposition of materials, RIE (Reactive Ion Etchers), used in the semiconductor industry. Figure 2.15 shows one of these systems.

Sirus T2 RIE desktop camera by TRION TECHNOLOGY.